Where Art meets Activism

“Art is a material act of culture, but its greatest value is its spiritual role, and that influences society, because it’s the greatest contribution to the intellectual and moral development of humanity that can be made.”

- Ana Mendieta

Artivism is where art meets activism. Art has the ability to raise awareness and to tell stories; art can reflect back at us the world we live in, oftentimes with greater clarity or nuance. Art can also depict visions of the future, and shed light on histories and cultures gone by, both key to reimagining the world we want to cocreate.

But beyond raising awareness and contributing to storytelling, art can play an active role in effecting change.

“When you start looking closely, every successful activist movement involves creativity, culture, and innovation. What we realized in the end is that *all successful activism is artistic activism*.” - Steve Duncombe, co-founder of The Center for Artistic Activism for Art and Object.

Whilst there has been increased interest in the concept of artivism, with a rise in subvertising - a portmanteau of subvert and advertising - and social media enabling the rapid and widespread sharing of creative images, the intersection of art and activism has always existed. Throughout history, art has served as a powerful vehicle to send messages of solidarity, statement, expose injustices and urge reform.

Here’s just a few examples of famous artivism:

The Uprising | Diego Rivera (1931)

In the early 1930s, an era of widespread labor unrest, images of the violent repression of strikes would have resonated with both U.S. and Latin American audiences. The battle here stands as a potent symbol of universal class struggle. For left-leaning artists in New York, the frescoes Rivera made for The Museum of Modern Art provided a powerful model of modern, socially engaged art with content rooted in Marxism. Later in the 1930s comparable images of strikes by U.S. artists, specifically referencing the hunger and unemployment issues that plagued the country at the time, became increasingly commonplace. (From MoMA)

American Gothic | Gordon Parks (1942)

American Gothic is a portrait of Ella Watson, who symbolizes the American black worker. This photograph references the style and composition of the American artist Grant Wood's classic painting of the same title.

Parks' recreation makes visible the often invisible labor performed by so many African-Americans in both rural and urban America, capturing the essence of activism and humanitarianism in mid-twentieth century America. This photograph, one of Parks' most famous works, was not only an indictment of America, but even more so a challenge to the nation to live up to its magnificent creed "...that all men are created equal." (from The Art Story)

"My purpose has been to communicate - to somehow evoke the same response from a seamstress in Harlem or a housewife in Paris." - Gordon Parks

The Artifact Piece | James Luna (1987)

In 1987, Luna laid down in a vitrine at the Museum of Man in San Diego. He wore just a loin cloth and was surrounded by objects including divorce papers, records, photos, and his college degree.This performance came to be known as “Artifact Piece.” Luna was commenting on the standard museum practices of presenting indigenous cultures as natural history (objectifying instead of humanizing, presenting difference as curiosity) and of the past (implying indigenous people and cultures no longer exist). Luna was a living and breathing human in the exhibit, challenging the idea that native people are extinct. (from Marabou at the Museum)

Guernica | Pablo Picasso (1937)

Probably Picasso's most famous work, Guernica is certainly his most powerful political statement, painted as an immediate reaction to the Nazi's devastating casual bombing practice on the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Guernica shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals, particularly innocent civilians. This work has gained a monumental status, becoming a perpetual reminder of the tragedies of war, an anti-war symbol, and an embodiment of peace. (from Pablo Picasso Org)

“Painting is not made to decorate apartments. It's an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.” - Pablo Picasso

Study of Perspective - Tiananmen Square | Ai Weiwei (1995)

Ai Weiwei, a Chinese artist confined, punished and unable to experience full freedom himself, has often spoken out against human rights abuses and the need for reform. Study of Perspective is a series of images, shot from 1995 to 2003, showing the artist flipping the middle finger against different places across the globe—many of which are iconic landmarks of their respective countries. The gesture, captured utilizing a snapshot aesthetic, confronts its viewer with a universal and concise statement of political opposition. (From Contemporary Art Curator)

Past Times | Kerry James Marshall (1997)

Having lived near the headquarters of the Black Panthers, Marshall’s art typically reflects the reality of many working-class African Americans, painting scenes of his neighborhood community. Past Times, however, depicts a black family in high-class leisure – playing golf, playing cricket, as well as water skiing and driving a motorboat across a lake. It’s a take on a pastoral scene typically filled with European aristocratic types yet instead filled with black figures. (From The Guardian)

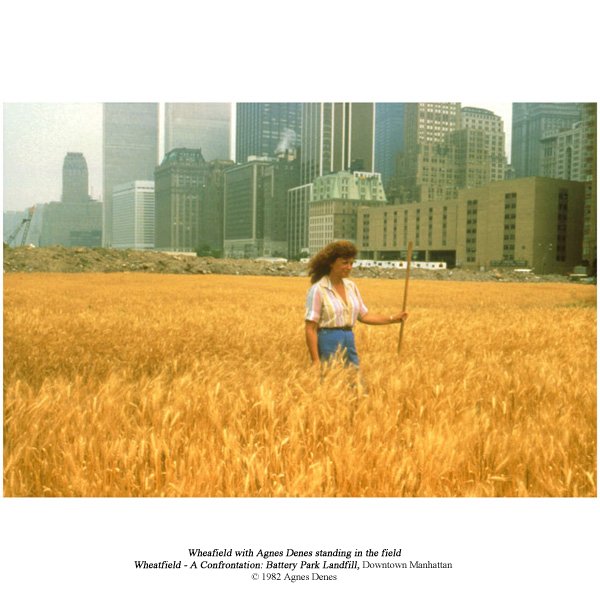

Wheatfield - A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan | Agnes Denes (1982)

In May 1982, a 2-acre wheat field was planted on a landfill in lower Manhattan, two blocks from Wall Street and the World Trade Center, facing the Statue of Liberty. Two hundred truckloads of dirt were brought in and 285 furrows were dug by hand and cleared of rocks and garbage.

Planting and harvesting a field of wheat on land worth $4.5 billion created a powerful paradox. Wheatfield was a symbol, a universal concept; it represented food, energy, commerce, world trade, and economics. It referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns. It called attention to our misplaced priorities. After harvesting the seeds were carried away by people who planted them in many parts of the globe. (from Agnes Denes Studio)

Read more on money, economics and climate change under our topic New Economies

Embassy | Richard Bell (2013)

Richard Bell’s Embassy project has travelled the world since it was first mounted in Melbourne in 2013. The installation consists of a large military-style canvas tent surrounded by painted protest signs with slogans such ‘White Invaders You Are Living on Stolen Land’; ‘…Why! Preach Democracy’ and ‘…We Wuz Robbed’. A sign marks the tent as ‘Aboriginal Embassy’, and the public are invited to enter and watch a screening of Alessandro Cavadini’s film Ningla A-Na (1972). This historically significant documentary tells the story of Aboriginal activism in south-eastern Australia in the 1970s, establishing Embassy as a public space for imagining and articulating alternate futures and reflecting on, or retelling, stories of oppression and displacement. (From Museum of Contemporary Art Australia)

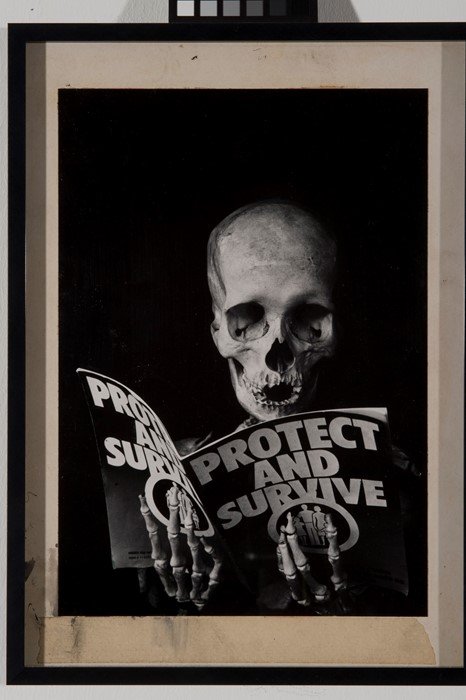

Protest and Survive | Peter Kennard (1980)

Kennard began to use the technique of photomontage when involved in anti-Vietnam War activities. It became his signature style, which he has used to produce some of the iconic images of modern anti-nuclear and anti-war protest. These strong and memorable monochrome images have been widely circulated in poster form. In the 1980s, Kennard worked with organisations including CND, the Labour Party and the Greater London Council. (from Imperial War Museum)

Poster for the Black Panthers | Emory Douglas (1969)

Emory Douglas was an integral part of the Black Panther Party, joining as minister of culture in 1967 and designing artwork that became potent symbols of the movement. His collection of newspaper illustrations, posters and pamphlets all bear his trademark imagery, and hard-hitting slogans, which inspired many to act. (from The Guardian)

Stolen Climate | Clinton Naina (2020)

Clinton Naina’s work: Stolen Climate, composed under Melbourne’s 2020 lockdown, [is] a deeply emotional response to bushfire, coral bleaching and climate change, and the colonial thread that weaves underneath them. (From Sydney Morning Herald)

“I was looking at who I identify as and where I come from, and what is happening to that country. These issues are global. Stolen climate is just another part of colonisation, imperialism, capitalism.” - Clinton Naina

Untitled (Birmingham, Alabama) | Andy Warhol (1964)

In May 1963, photographers swarmed to catch a glimpse of civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama. Their cameras documented harrowing scenes such as this one, in which a man is trapped between police dogs attacking him from two directions. Andy Warhol used a photograph from Time magazine as the source of Untitled (Birmingham, Alabama). He increased the contrast of light and dark to eliminate details and emphasize the moment’s tension. The resulting print casts a light on the gulf between nonviolent protestors and local authorities at the time. (from Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Ice Watch | Olafour Eliasson (2014)

For Ice Watch (2014), the Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson extracted 30 blocks of glacial ice from the waters of Greenland and in 2018 strategically placed them in front of Tate Modern in London. The ice was left here to melt. Ice Watch was to inspire public action against climate change, advocating for a rapid public response. (From Public Delivery)

Human Cost | Liberate Tate 2011

Liberate Tate was founded during a workshop on art and activism, commissioned by Tate, in January 2010. It aimed to take creative disobedience against Tate until it dropped its oil company funding. Human Cost was a performance at the Duveen Gallery, Tate Britain, that took place on the first anniversary of the start of the BP Gulf of Mexico disaster. It lasted for 87 minutes, one for every day of the spill. [In 2016] BP announced it was ending its Tate sponsorship after 26 years, citing a ‘challenging business environment’. (From The Guardian)

Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants) | Ana Mendieta 1972

By gluing her friend's beard onto her (female) face, Ana Mendieta highlighted the fact that sexual classifications are social conventions that frame and overdetermine sexualities. The artist problematized those classifications and disrupted the normative models of beauty by which society operates, differentiating between the feminine and the masculine. (from Hammer Museum)

Grace of The Sun | Robert Montgomery (2021)

Grace of the Sun was a solar powered light poem urging commitment to renewable energy at the UN climate conference (COP26). The artwork was constructed using 1,000 solar powered Little Sun lamps. During COP26 it illuminated every day at sunset as a poetic beacon of hope for Glasgow. (From the Robert Montgomery Org)

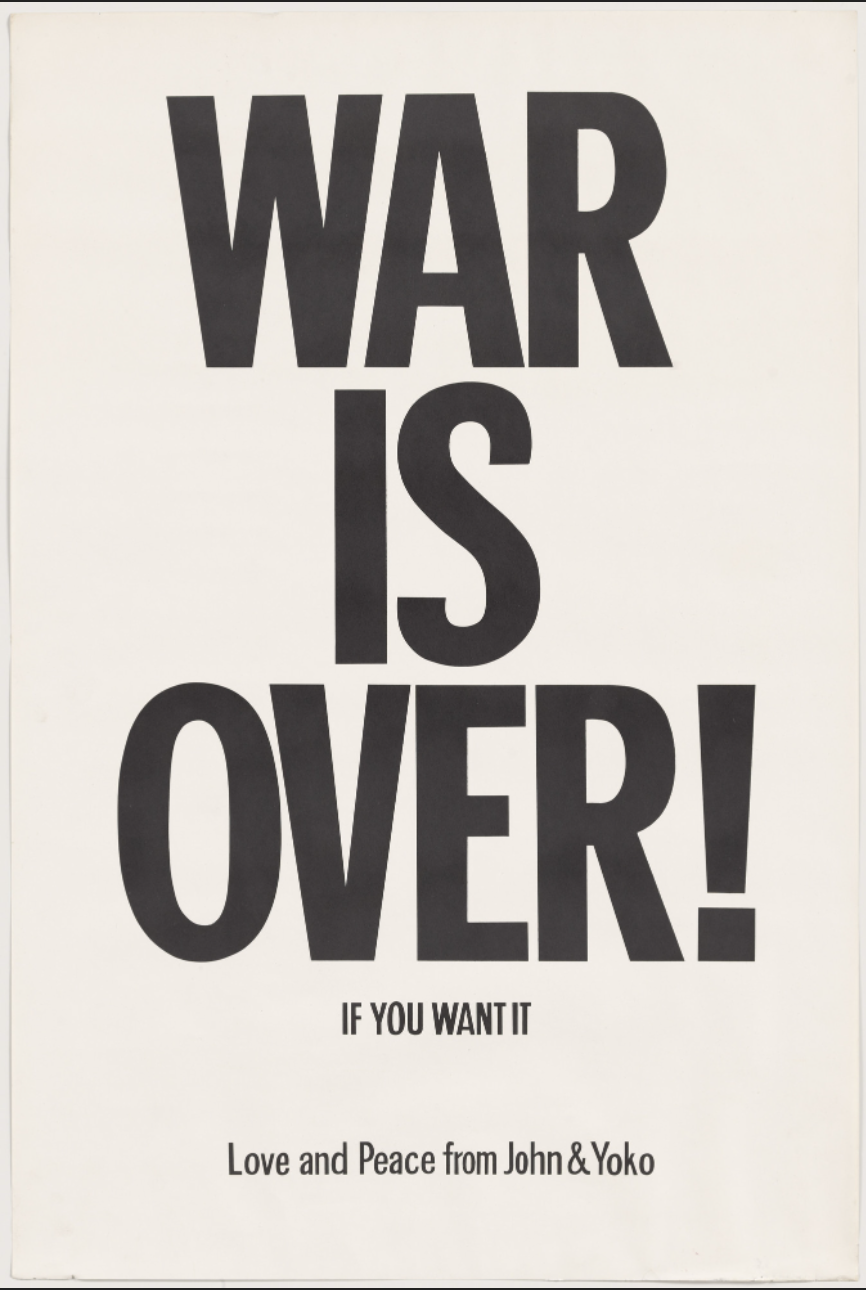

WAR IS OVER! if you want it | Yoko Ono and John Lennon (1969)

Deliberately intended to draw the crowds and reach as many people as possible, Yoko Ono & John Lennon made use of leaflets, posters, radio announcements, newspaper advertisements and billboards to send a message of self-responsibility for peace. By presenting it (peace), like something which people could touch and interact with, their sole mission was to get everybody’s attention drawn to the fact that war and peace are their choice. (From Public Delivery)

Reclaiming the Monument | Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui (2020)

Reclaiming The Monument is a projection based protest art project headquartered in Richmond, Virginia, whose body of work addresses systemic racism, human rights, and historical narratives through public art. This project was founded by artists Dustin Klein and Alex Criqui in the wake of the death of George Floyd, as a spontaneous reaction to the violence the artists witnessed around the nation and in their own city. By utilizing the peaceful and nondestructive medium of light, the two artists hoped they could amplify the voices of the movement around them. (From Reclaiming the Monument)

“Our goal is to continue to address the neglected historical and social narratives in our community and in communities around the world through projection based art, and to help put the tools, knowledge, and skills we utilize in our own work into the hands of others to create greater access to utilizing light as a peaceful means of protest and resistance.”

Follow EcoResolution on Instagram as we platform more artists and cultural objects that help forefront justice, build movements, inspire imagination, and empower action.