Good COP, Bad COP: A History of Climate Negotiations

Author: Lara Steele

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was first established in 1992 and committed 197 nations to avoid dangerous human interference with the climate system.

Since then, world leaders have met annually at the UNFCCC Conference of Parties, or COP, to achieve these goals. After 25 meetings spanning over two decades, what has been achieved? Here, we explore some of the most notable meetings, from the good, the bad and the ugly…

The first step: Berlin, 1995

The Berlin Wall might have seen its demise, but the walls dividing countries seemed a difficult barrier to cross at the first climate negotiations in Berlin in 1995. Anyone with high hopes of COP saving the planet were left disappointed after a fortnight of endless discussions terminated with no concrete protocols or treaties. What Berlin did achieve, however, was to pave way for future meetings particularly through the establishment of the Berlin Mandate which acknowledged the inadequacy of the current UNFCCC convention and initiated a process to agree to binding targets to come into force after 2000. While not a huge step, it was a still a step in the right direction.

The good and the bad: Kyoto Protocol, 1997

The first milestone achieved by COP was the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. The Protocol was the first to make emissions reductions part of international law. Hence, it marked a more dedicated commitment to combatting climate change by many of the world’s key nations.

Under the Protocol, which came into force in 2005 when it finally reached 55 signatories, industrialized nations pledged to reduce their carbon emissions by 2012 compared to their respective 1990 levels. Those termed ‘developing countries’ on the other hand were excluded from any targets in light of their recent history in polluting compared to the historical responsibility of ‘developed countries’.

At a first glance, the Kyoto Protocol appears to be a huge success… However, the Protocol lacked both depth and width; it made it too easy for countries to meet their targets without real change. By allocating a monetary value to greenhouse gas emissions, trading enabled countries to compensate for their continued emissions, without making any real changes.

In order to meet the emissions reduction targets countries could use natural “sinks”, such as afforestation projects, that absorb carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. The Protocol established The Clean Development Mechanism to promote investment in renewable technologies in the developing world. Under this mechanism, industrialized countries could fund technologies or infrastructure in developing countries and claim the reduction in emissions as their own. Finally, the Protocol created a market for trading emissions by allocating a monetary value to greenhouse gas emissions which countries could then buy or sell to others in order to compensate for their emissions.

At a first glance, the Protocol appears to be a huge success; especially in light of the 12.5% reduction in CO2 emissions that occurred between 1990 and 2012. However, the Kyoto Protocol lacked both depth and width; it made it too easy for countries to meet their targets without real change, and its success was greatly limited by one major drawback; the world’s biggest polluters, China, India and the US, were not signatories of the Protocol. China and India were exempt on the basis of their status as developing countries and the US never ratified the treaty because of the economic impacts. This meant that the 12.5% reduction in CO2 emissions by participating countries was rendered entirely insignificant by the US and China polluting more greenhouse gases than was saved.

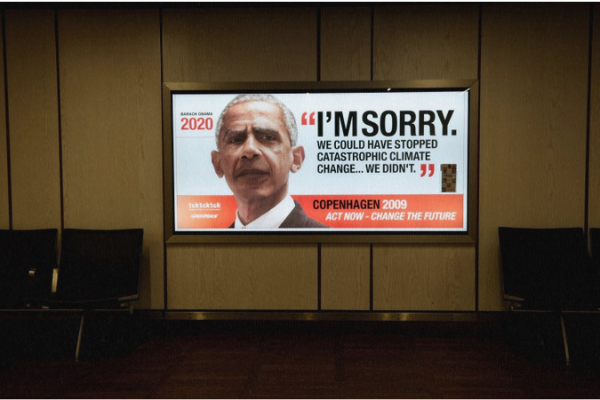

The Cop-Out: Copenhagen, 2009

If the Kyoto Protocol seemed like a promising start to pave the way for future agreements, climate negotiations reached a historical low point at Copenhagen in 2009. Negotiations were hindered by so-called ‘developing and developed’ countries each calling on the other to play a larger role. This dynamic of avoiding responsibility resulted in a stalemate that was resolved last minute with the cobbled together Copenhagen Accord.

The Accord “recognizes” the scientific case for keeping temperature rises to no more than 2C but offered no concrete means of achieving this other than allowing countries to set their own emissions targets for 2020. However, there was some success as the Accord set up a forestry deal aimed at reducing cutting forests for cash and established an objective to provide $30 billion to developing countries to adapt to climate change.

With many of the countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change expecting a more substantial agreement, the Accord was a disappointing last-minute reprieve to avoid the failure of having achieved nothing at all. The UK PM at the time, Gordon Brown, might have said the Accord was a “vital first step”, but how many first steps were there going to be before real commitments were made?

Images from a 2009 Greenpeace campaign in the run up to COP15 depicting contemporary world leaders including Harper (Canada), Merkel (Germany), and Obama (USA) imagining them apologising in 2020 for not taking action in 2009.

We’ll always have Paris?: the Paris Agreement, 2015

Faith and optimism were restored in COP in 2015 when cheering erupted upon the conclusion of the Paris Agreement; a shinier, new and improved agreement that replaced the Kyoto Protocol. Inclusivity was the key strength of the Paris Agreement; 196 nations and many other non-state actors participated in the agreement which, for the first time, committed all countries to emissions targets and not just ‘developed’ nations. The mood following its establishment was one of high hopes and promise as Remy Rioux, who led the talks as part of the French movement team said, “the Paris agreement is a powerful signal of hope in the face of the climate emergency.”

Under its terms, signatories pledged to hold global warming below 2C and an aspiration of keeping it below 1.5C. In order to achieve this, each country set their own emissions targets known as National Determined Contributions, or NDCs, which are reviewed every 5 years to keep them on track with the global target. It also pledged a fund of $100 billion by 2020 which would be replenished annually to help developing countries mitigate climate change and invest in renewable energy .

“The Paris agreement is a powerful signal of hope in the face of the climate emergency.”

Even Trump announcing his intention to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement in 2017, did nothing to sway the commitment of the rest of the world to meet their targets. In fact, there has since been a wave of nations introducing their own long-term net-zero emissions targets including Norway, Chile, Japan and most surprising of all, China. These commitments combined with the US rejoining the Paris Agreement this year under Biden, indicate a stronger, more united commitment to preventing climate catastrophe.

The Copenhagen Copy: Madrid, 2020

Just as Copenhagen was seen as a huge flop following the success of Kyoto, Madrid did the same for Paris. The aim at Madrid’s meeting was to create a framework to straighten out the technicalities of the Paris Agreement including the creation of a financial mechanism for carbon trading. None of its aims were achieved in the watered-down final text which did little more than establish some vague pledges to step up current emissions targets.

With COP26 on the , hopes are high that this year’s meeting in Glasgow can fix the unsolved issues left over from last year in Madrid.

So: good COP / bad COP?

On one hand, COP appears to have achieved very little: It has taken nearly 30 years to establish an agreement that keeps global warming at too high levels and currently provides no mechanism to ensure compliance. That’s without taking into consideration the 60,000 tonnes of CO2 produced by each meeting through the aviation, heating and power needed to gather 20,000 people from around the world to discuss saving the planet. Whilst the world has shied away from responsibility, global warming has ramped up to more than 1C above pre-industrial levels causing a notable increase in extreme weather.

COP, however, may not be perfect and its achievements shadowed by its failures, but the Paris Agreement and COP itself still remain our best hope to avoid catastrophic climate change. We cannot fix a global threat through national action alone and COP serves to bring the global community together to collaborate and maintain climate change on the agenda. Does more need to be done to avoid a climate catastrophe? Most definitely, and the science agrees. This boils down to the recurring question: Is it better to have something that is flawed but does something, or do nothing at all? Is it better to act and organise imperfectly, rather than not to act at all?

References

About the Secretariat (UNFCCC)

Conference of the Parties 1, Berlin Mandate (Down to Earth 1995)

Berlin Mandate (Encyclopedia.com)

What is the Kyoto protocol and has it made any difference? (The Guardian 2011)

Kyoto Protocol, International Treaty 1997 (Britannica)

The Kyoto Protocol: Climate Change Success or Global Warming Failure? (Circular Ecology 2015)

Low targets, goals dropped: Copenhagen ends in failure (The Guardian 2009)

Copenhagen climate deal: Spectacular failure - or a few important steps? (The Guardian 2009)

The Paris agreement five years on: is it strong enough to avert climate catastrophe? (The Guardian 2020)

Trump Will Withdraw U.S. From Paris Climate Agreement (NY Times 2017)

What is the Paris climate agreement and why did the US rejoin? (BBC 2021)

US rejoins Paris accord: Biden's first act sets tone for ambitious approach (BBC 2021)

Why did COP 25 Fail? (Future Bridge 2020)

Failure In Madrid As COP25 Climate Summit Ends In Disarray (Forbes 2019)

Climate crisis: what is COP and can it save the world? (The Guardian 2019)

Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures (Council on Foreign Relations 2021)

Images

UNFCCC Flickr

UN Major Group for Children and Youth

Greenpeace via Osocio