The Suffragettes, UK

Deeds, not words: Civil disobedience and the story of women’s suffrage

In 1906, a reporter writing in the Daily Mail created the label suffragette in order to belittle the women advocating women's suffrage. The women at the Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU) embraced the new name, and adopted it as the title of their published newspaper.

What is Suffrage?

Suffrage is the right to vote in political elections. The suffragists were members of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and were lead by Millicent Garrett Fawcett during the height of the suffrage movement, 1890 – 1919.

They campaigned for votes for middle-class, property-owning women and believed in peaceful protest. Millicent thought that if the organisation was seen to be thoughtful, intelligent and law-abiding, that they would win the respect of Parliament and in time, be granted the vote.

“It’s natural to continue to restore forest nature from the restoration of aquatic nature, as both are interconnected. We develop concrete, placebased models to restore nature’s own ways of repairing itself. The traditional knowledge of the Skolt Sámi and the latest climate science open up new horizons of activity in parallel.”

— Pauliina Feodoroff, Skolt Sámi Project Coordinator

So, Why the Suffragettes?

Emmeline Pankhurst was a former member of the NUWSS and a supporter of women’s suffrage. In 1903, after becoming frustrated with the Suffragists’ approach, she broke off and formed her own society – the Women’s Social and Political Union. The society was more inclusive and welcomed women from all different walks of life. Emmeline’s daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, were also active in the cause.

Under the banner "Votes for Women", the suffragettes engaged in direct action and civil disobedience as they fought for the right to vote in public elections.

“We have to document and to show that we had a sustainable system of using lands. But we can ask a critical question: What is the origin of these damages we are addressing.”

— Pauliina Feodoroff, Theatre Director, Artist & Nature Guardian

From Words to Deeds

In 1865 John Stuart Mill was elected to Parliament and in 1869 he published his essay in favour of equality of the sexes The Subjection of Women.

Also in 1865, a women's discussion group, The Kensington Society, was formed. Following discussions on the subject of women's suffrage, the society formed a committee to draft a petition and gather signatures, which Mill agreed to present to Parliament once they had gathered 100 signatures.

In October 1866, one of the organisers of the petition, Barbara Bodichon, read a paper entitled Reasons for the Enfranchisement of Women at the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science held in Manchester

But after 38 years of essays, papers and petitions, the suffragettes decided it was time for action…

When by 1903 women in Britain had still not been enfranchised, Pankhurst decided that women had to "do the work ourselves"; the WSPU motto became:

"DEEDS, NOT WORDS"

“You cannot muck around on the river. River used to be sacred before. You needed to thank her if you received something.”

— Jouni Moshnikoff, Skolt Sámi Fisherman

What Did Their Direct Action Look Like?

The suffragettes heckled politicians, tried to storm parliament, chained themselves to railings, smashed windows, set fire to postboxes and empty buildings, and damaged property.

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney, disrupted speeches by prominent Liberals Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, asking where these male politicians stood with regards to women's political rights. When the women unfurled a "Votes for Women" banner they were both arrested for a technical assault on a policeman. When Pankhurst and Kenny appeared in court they both refused to pay the fine imposed, preferring to go to prison in order to gain publicity for their cause.

What Was the Response at the Time?

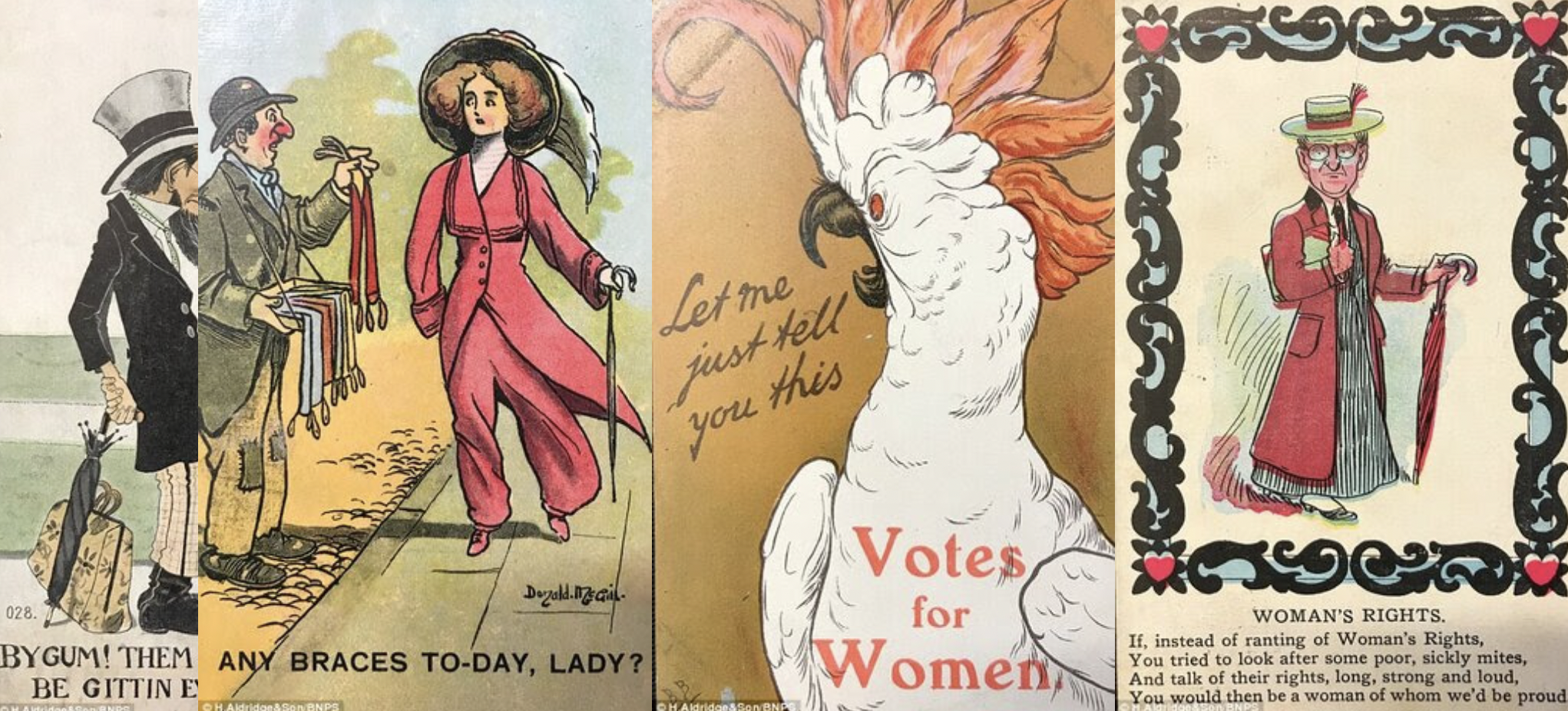

One immediate response was ridicule and belittlement from multiple sources: in popular media, postcards, newspapers, parliament, and even in their own homes and social circles.

One form of ridicule was the recurring stereotypical image of the strong minded woman in masculine clothes created by newspaper cartoonists. In response, the suffragettes resolved to present an overly fashionable and exaggerated feminine image when appearing in public.

Worse yet, beyond having to face anger and ridicule in the media, many were attacked and sexually assaulted during battles with the police. When imprisoned many of the suffragettes went on hunger strike, to which the government responded by force-feeding them. The first suffragette to be force fed was Evaline Hilda Burkitt.

What’s the Controversy About Non-Violent Direct Action?

1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes, as many suffragettes turned to using more militant tactics: whilst unattended, places that wealthy people (typically men) frequented were burnt and destroyed, including cricket pavilions, horse-racing pavilions, churches, castles and the second homes of the wealthy. The suffragettes also burnt the slogan "Votes for Women" into the grass of golf courses. Here, the goal was to attack the property of wealthy men, but to ensure minimal risk to life. Many historians and contemporaries however, would argue that the use of bombs, fire and the destruction of property were violent, or potentially violent.

Opponents at the time also criticised the use of direct action and civil disobedience on the grounds that it was supposedly evidence that women were too emotional and could not think as logically as men.

However, in her 1914 autobiography, Emmeline Pankhurst wrote:

“Men make the moral code and they expect women to accept it. They have decided that it is entirely right and proper for men to fight for their liberties and their rights, but that it is not right and proper for women to fight for theirs.”

One of the most significant moments within the suffragette movement and their direct action was the death of one suffragette, Emily Davison. When Davison ran in front of the king's horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby, this event made headlines around the world.

What Was the Outcome?

So, was the movement a success? One of the supposed successes was the creation of the Representation of the People Act which was introduced in 1918. Whilst this act extended the vote to all men over 21, and to some groups of women over 30, this act still presented obvious inequities, continuing to discriminate according to social-class, gender, and age. Furthermore, several historians have suggested that the creation of this Act was a move made by the government which hoped that these upper-class women over 30 would be a 'moderating' influence on radical younger male voters and would also take the heat out of the female suffrage movement.

Following this Act, more than half of women still did not have a say in electing their government. Campaigning continued therefore until 1928 when women were finally granted the vote on equal terms to men.

Whilst the suffragette movement pushed for women’s suffrage, the backlash and response that the movement provoked indicates that this was a movement about much more than just the ability to vote. “The suffrage campaign was a long campaign, taking 52 years from 1866 to 1918, because it was ultimately about changing people’s attitudes about women,” says Gillian Murphy, Curator for Equality, Rights and Citizenship, and who looks after the Women’s Library collection at the London School of Economics Library.

Was this NVDA Movement Inclusive?

Conversation in recent years has turned to the diversity of the British suffragette movement, particularly in terms of race and sexuality. In particular, following the release of the 2015 movie Suffragette, many felt that the movement has been ‘white-washed’, with some of the key leaders of the movement being overlooked. Sumita Mukherjee, a historian of the British Empire and Indian subcontinent, has spoken about the Indian women who were actively involved in the British movement, and would go on to play significant roles in the Indian suffrage movement.

In 2015, following the release of the Suffragette movie, Anita Anand, author of Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary, spoke to the New Statesman about the women of colour working alongside more famous white suffragettes, most notably the subject of her book, the Indian princess Sophia Duleep Singh:

“There were many overlaps between the Indian suffrage movement and the British suffrage movement. Sophia Duleep Singh had every reason to hate the British. They had taken everything from her: her father’s kindgom, wealth, future, everything. But she believed in this sisterhood, and she sacrificed everything to fight for British women’s vote, and also then fought for Indian women’s emancipation as well.”

Following the British suffragette movement, many women post-1918 did start looking outward and thinking about suffrage around the world, but Mukherjee says that this must be taken in context with the “complicated history around imperialism and the objectification of women of colour in the movement.”

So, Was NVDA Effective?

The destruction of property continues to be a contentious point when discussing violence, and some of the militant tactics of the suffragette movements can be seen as non-violent, and some as violent. One of the key arguments for NVDA, however, is that it can be a more inclusive movement, with those that would be deterred by the possible risk of violence able to contribute to the movement.

As a prolonged movement, which became about much more than women’s suffrage, the suffragette movement can be seen as embracing this inclusivity. Whilst the suffragists fought for the women’s vote through petitions, conversations, and through the societal mechanisms already in place, the suffragettes undeniably fought to change the prevalent presentations of women as submissive, ‘refined’, and ornamental components of society. This required becoming a movement for the working-class, for the young and the old, for people of colour, and for those consistently marginalised. The supposedly civilised mechanisms of society already in place actively excluded these marginalised demographics: whilst historians may continue to debate whether the suffragettes are responsible for women’s suffrage, we believe it is undeniable that the shift in attitudes towards women would not have taken place without their direct action and civil disobedience.

Sources and Further Reading:

Holton, Sandra Stanley (November 2011). "Challenging Masculinism: personal history and microhistory in feminist studies of the women's suffrage movement". Women's History Review. 20 (5): (829–841), 832. doi:10.1080/09612025.2011.622533

Pankhurst, Christabel (1959). Unshackled: The Story of How We Won the Vote. London: Hutchison

"John Stuart Mill and the 1866 petition". UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 February 2018

"Mr. Balfour and the 'Suffragettes.' Hecklers Disarmed by the Ex-Premier's Patience." Daily Mail, 10 January 1906

"SUFFRAGETTES". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 16 April 1913. p. 7. Retrieved 26 October 2011

Porter, Ian. "Suffragette attack on Lloyd-George". London walks. London Town Walks. Retrieved 4 February 2013

Fawcett, Millicent Garrett. The Women's Victory – and After. p.170. Cambridge University Press

"Did the Suffragettes Help?". Claire. John D. (2002/2010), Greenfield History Site. Retrieved 5 January 2012

https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/did-the-suffragettes-win-women-the-vote/z7736v4

https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/feminism/2015/10/what-did-suffragette-movement-britain-really-look

https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/history/general-history/suffragettes-facts/?awc=19533_1601375934_103d6681d08c214806ff7cbbf4209b1d